Glossary, Research Data, and Technical Resources

Table of Contents (Links are not active at this time)

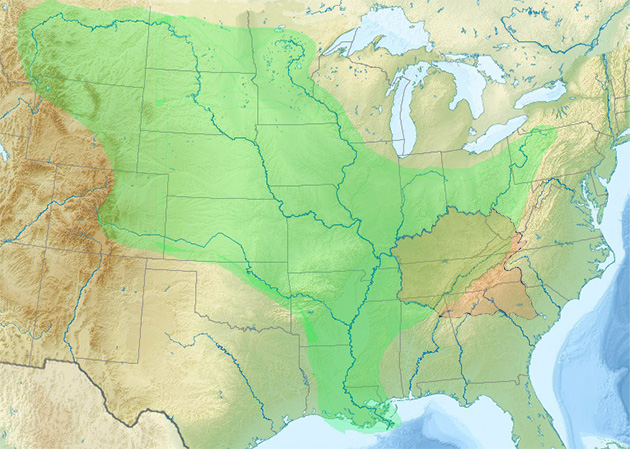

North America at the End of the Ice Age

The Collapse of the Hopewell Exchange System

In 1759, 17 years before the American Revolution, the British Governor at Charles Town and a delegation of Cherokees negotiated a treaty which described the territory of the first independent nation in the Americas.

The Treaty of 1759 called for:

- an end to hostilities between the Cherokee and the British colonies,

- British recognition of Cherokee control of a vast territory encompassing most of Kentucky and parts of the Carolinas, Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama,

- Cherokee agreement to kill or capture French soldiers and civilian sympathizers found within the treaty borders, and

- surrender of 24 individual Cherokees to British justice.

In addition, the Cherokee were encouraged to use their diplomatic and military influence in Ohio to undermine the French alliance with the Ohioan Delaware, Shawnee, and Iroquois (Mingo) people.

This work is intended as an introduction to the pre-history of the Cherokee Nation, the first independent nation in the New World. It is drawn primarily from archaeological research done in the 19th and 20th centuries, and covers the time from human entry into Eastern North American until written historical records were produced after European contact. References to the Cherokee Nation in this work refer to the territory outlined in the Treaty of 1759, and not to the jurisdiction of any modern Cherokee government.

The Cherokee Nation of 1759 didn’t last long. There was no central government and the Cherokee lacked enough soldiers to defend its vast claims. Its territory was steadily invaded by British and then American settlers, and the Cherokee were induced to cede land steadily in a series of treaties.

Although it existed for only a short time, the Cherokee Nation of 1759 provides a useful framework for exploring the history of Eastern North America. In this work the term “Cherokee Nation” is the territory outlined in the Treat of 1759, and not any of the modern Cherokee governments.

Appalachian Summit and the Nation of 1759

Eastern North America, stretching from the Mississippi drainage to the Atlantic Ocean, has temperate weather, abundant rainfall, and some of the most productive land in the world.

The highest part of Eastern North America is the Appalachian Mountains, once higher than the Himalayas. The Appalachian Summit, which includes the Appalachian Mountains and highlands, is one of the defining features of the Cherokee Nation.

The rugged terrain was drained by smaller rivers and had smaller patches of flat land than the Mississippi drainage to the north and west.

Because of its large variations in elevation, the Appalachian summit provided a variety of ecosystems and habitat for deer, small game, and a variety of indigenous plants.

The first people came into North America toward the end of the last (Wisconsinan) ice age when temperatures rose about 10o F; the Wisconsinan ice sheet retreated northward; and spruce and fir forests were replaced by warmer adapted mixed pine and hardwood trees.

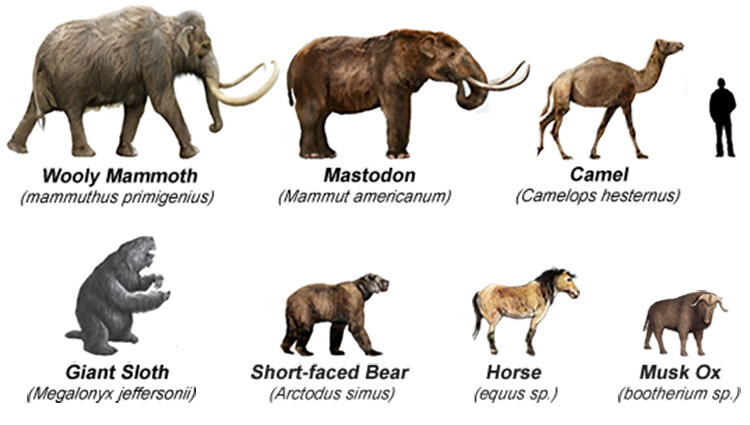

Many ice age animals, including camels, mammoths, mastodons, and horses, were unable to adapt to the post-glacial ecosystems and became extinct by 10,000 years ago.

All potential draft and pack animals were gone, and for the next 9,500 years, everyone in North America traveled on foot or by watercraft along the 25,000 miles of navigable waterways in North America. The largest component of the North American river system, the Mississippi Drainage, is the third largest river system in the world. Bostick 2017; Wikipedia 2019f

About 35,000 years ago, the cold-adapted Upper Paleolithic Culture spread through northern Asia and reached the sunken land bridge of Beringia. Traveling in small groups through Beringia and along the Pacific coast, people we call the Paleo-Indians entered North America about 20,000 years ago. This settlement was carried out over thousands of years by groups who came from Siberia and northwest Asia. The Paleo-Indians spread quickly throughout the unoccupied American continents, reaching Eastern North America and the southern tip of South America before 15,000 years ago. (Adovasio et al. 1990; Anderson 1991; Kelly 1983; Kelly and Todd 1988)

The Paleo-Indians were nomadic hunter gathers who moved regularly as they followed game and gathered wild plants. They never settled in one area long enough to become expert in local plants and animals, and there were never many of them. Paleo-Indians probably lived in bands of less than 100 closely related people who met other bands seasonally to gossip, court potential mates, and trade tools and other valuables.

Megafauna found in Saltville Valley, Virginia.

(Schubert and Wallace 2009; S. Wikipedia 2019a)

About 13,000 years ago, Paleo-Indians began using fluted Clovis points on their spears. The fluted point style swept across most of North America in less than 500 years. Fluted points allowed split shaft to extend nearly to the tip of the point, limiting the extent of point breakage and allowing fluted points to be reworked more often and firmly mounted even when shortened by breakage and resharpening. Fluting reduced the risk of running out of points during extended hunting trips far from known high quality lithic sources.

About 12,500 years ago, at the end of the last (Wisconsinan) Ice Age, temperatures rose and mixed pine and hardwood forests replaced spruce, and larch trees over much of the Southeast.

Perhaps due to their inability to adapt to the new ecosystem, most megafauna were extinct in North America by 10,000 years ago. Although the megafauna couldn’t adapt, the Paleo-Indians did, and human culture changed. People began to focus on hunting deer and small game, and gathering nuts, berries, seeds, and other food in the modern pine and hardwood forests.

As hunting strategies changed, so did hunting weapons. Fluted points from distant deposits were replaced by non-fluted Dalton and Kirk points made from local stone.

As point styles changed, other tools, such as scrapers and blades, remained the same, suggesting that the new point styles were adopted by the local people rather than brought in by newcomers with different tool styles. (Griffin 1967)

To the south and east of the Appalachian Summit, Archaic groups settled along the larger rivers and moved seasonally from summer camps in the Appalachians to winter camps near the Atlantic coast. There weren’t many people. During the Archaic Period, the total population of the Southeast Atlantic Zone is estimated to have been less than 1,500 people. (Anderson and Hanson 1988; B. J. Chapman and Adovasio 1977; Griffin 1967)

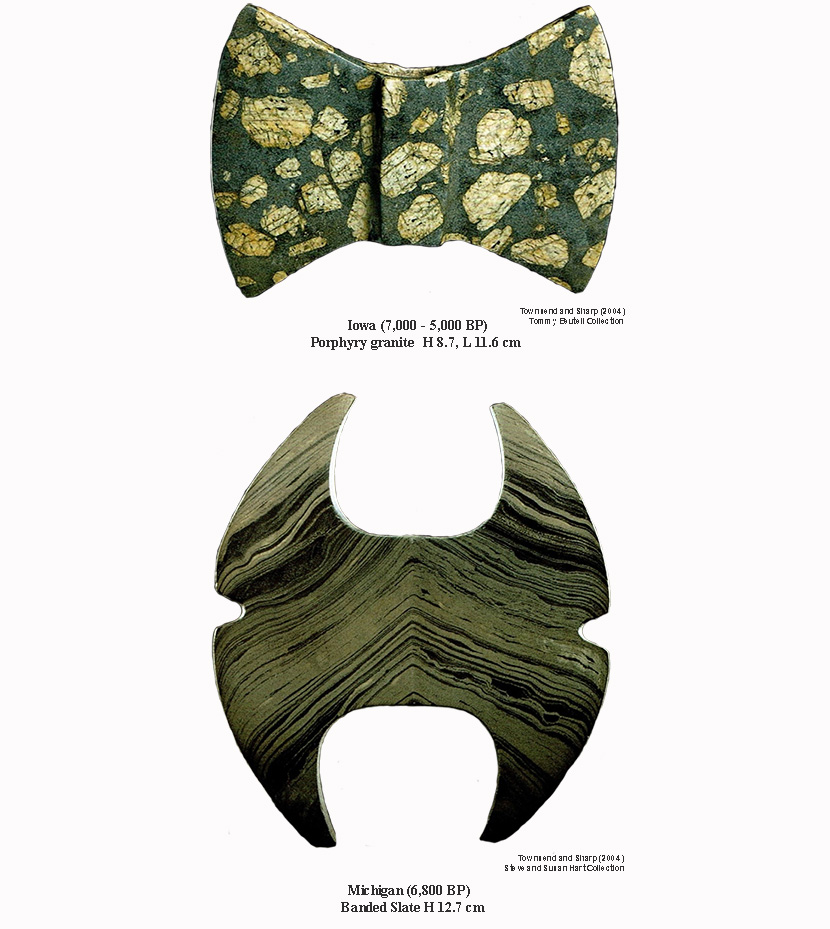

As more areas were settled, trade networks began to form along rivers and game trails, often intersecting at salt flats, springs, or quarries. Trade goods included beautiful stones which could be formed into art for display, ceremonial use, or further trade. One of the most widely traded items was the Bannerstone, which became widely traded about 7,000 years ago. Bannerstones were carved of stones chosen for their natural colors and patterns. The beauty of the stone, the craftsmanship, and the amount of labor required to carve them all suggest that they were prestige items. Although their exact purpose remains a mystery, they were often grave goods, and few show any sign of use. Bannerstones may have been atlatl weights, or symbols of alliances or authority.

Bannerstones

About 4,000 years ago, Bannerstones fell out of fashion as trade items and were replaced by Boatstones and Birdstones .

Birdstones are admired for their simplicity and beauty, but, as with Bannerstones, no one knows what they were used for. Birdstones have flat or concave bottoms and holes drilled in the front and rear to allow them to be attached to another object. Birdstones may have been atlatl weights or possibly to be worn or attached to shafts as totems. (Bostrom 2019; Fagan 2000, 2005; Ohio_History_Connection 2019a; Wikipedia 2019a)

The Smithsonian Birdstone was carved into an abstract shape called the Popeye type. Its enormous eyes perhaps signify great vision, which could assist its owner in hunting or combat.

By 6,000 years ago, the Old Copper Complex in north central North America had developed a metalworking technique of cold working nuggets of almost pure copper into weapons, ornaments, and tools

Cultivation of Indigenous Plants

By 4,000 years ago in Eastern North America, several wild plants were being gathered and carried home to seasonal camps where food was processed and seeds and nuts were ground. Grinding stones were burdensome for nomadic Paleo-Indians without pack animals to move, but the more sedentary Archaic people could form heavier food processing tools which be left in seasonal camps.

The added food provided by domesticated plants and food processing tools provided the nutrition required to support substantial population growth in bottomland areas. (Smith 1989; Smith and Yarnell 2009; Sullivan and Prezzano 2001; Wikipedia 2019b)

Mound Builders

Geometric Mounds are first seen about 6,500 years ago at Monte Sano in the Louisiana delta. There a hunter gatherer society began building gigantic geometric mounds, perhaps as social, religious, or trade centers for the widely scattered population. The mounds were not used for burials and no signs of nearby occupancy nearby have been found.

Earthworks of different types were built across much of Eastern North America for thousands of years. Other mound types, including effigy and platform mounds, and geometric mounds for astronomical observation, were built by the later Adena, Hopewell, and Mississippian cultures.

The Woodland Period

These new Woodland cultures developed in a variety of ecosystems and had a diverse food supply. Seasonal hunting and gathering camps, often at higher elevations, provided foods not always available in bottom land settlements.

Artist’s Drawing of an Adena Burial Mound

One of the most common motifs is the Hand and Eye. It symbolizes the portal through which the deceased enter the Path of Souls to the realm of the dead. The earliest known image of the Hand and Eye motif is from the Gaitskill Clay Tablet (L), recovered from Gaitskill Mound, Kentucky, in the northern part of the Cherokee Nation. The Moundville Rattlesnake disc (R) was created over a thousand years later in Alabama.

Shamans

The Adena Pipe (L) was buried with an elite man who wore a loincloth decorated with hundreds of shell beads and a bone and pearl beaded necklace. The Adena Pipe likely shows the hair-style, ear spools, and feather bustle of a shaman, who may be a dwarf. The Wray Figurine (R) shows a Hopewell shaman wearing a bear skin and head. In the shaman’s lap is a detached human head, with its hair flowing down between the shaman’s legs.

Other items recovered from Adena and Hopewell mounds include: Human skulls formed into face masks, bowls, rattles, and gorgets, as well as carnivore jaws modified to be worn in the mouth. (Baby 1956, 1961; Stewart 1995; Webb et al. 1966; Webb et al. 1974)

The Adena developed a trade network which exposed their traders to goods, technology, and ideas from a wide area of Eastern North America. Trade relies on trust, not power. If you bring valuables to trade, you must trust that your potential partners won’t just take them. One way to build trust is through a common value system. Shared beliefs allow strangers to more easily trust one another. (Harari 2014) p36

Adena Cult beliefs, including burial mounds and elaborate grave goods, proved very attractive to other people in the Ohio River valley and beyond. People living along wide areas of eastern North America blended the Adena belief system with their existing beliefs.

By 3,000 years ago, the Adena culture was dominant in eastern North America. The Adena had no apparent organized rivals, and there is no evidence of attacks on Adena villages. (Harari 2014) p36 (Webb et al. 1974)

Adena grave goods and burial mounds were seen to the west among the Havana in Illinois, and in the Southeast among the Hopewellian Santa Rosa-Swift Creek people of the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts, whose influence extended into sites in the territory of the Cherokee Nation.

Two technologies developed by Havana in Illinois, flint maize, and pottery capable of cooking it, spread from Illinois to Adena groups in Ohio and Tennessee. As the Adena adopted maize agriculture, their population grew and they became more focused on trade of exotic goods.

Add Garden Creek Hopewell Site to map below. Are these sites Adena or Hopewell?

Selected Adena and Hopewell Sites (3,500 – 1,500 BP)

About 2,170 years ago, the Havana people of Illinois changed the history of North America when they began cultivating a new strain of flint maize (Zea mays) capable of thriving in the colder climate of the upper Mississippi Drainage. Compared to indigenous crops, maize had greater yields per acre and high energy and protein content. An acre of maize could provide almost all the calories and protein needed to support one person for a year. Dried maize can be stored for years and provide a stable food source in hard times or used as seed corn to expand farmland or to trade.

Add these sites and the Appalachian highlands map into Mississippi Drainage Map

The Hopewell

The Hopewell Tradition was the spectacular end of the Cult of the Dead. The Hopewell version of the Cult was practiced by about 20 independent and distinct regional cultures who participated in a trading network which exchanged spiritual ideas, goods, and technology along an extensive network of waterways and trails spanning much of Eastern North America.

Burial Mounds

Both the Adena and the Hopewell constructed burial mounds, and some mounds were used by both cultures. Both cultures buried their dead according to status. Lower status people of both cultures were buried simply, without grave goods. The elite were treated quite differently.

The Adena placed the bodies of their elite in a burial lodge until only the skeleton remained. The deceased was reburied along with grave goods. The Hopewell cremated most of their elite along with burial offerings. The ashes were placed in a mortuary building which would be burned before a mound was built over the remains.

Some mounds contained the remains of hundreds of people who died over many generations, but some of the most ostentatious burials were found in small mounds. At the Hopewell Mound, one burial contained almost 300 lbs. of obsidian, 60 % of all the obsidian ever found in Ohio. (NPS 2018; Ohio_History_Central 2017; Rothschild 1979)

Geometric Mounds

Adena and Hopewell mound centers were likely used as meeting places for spiritual and social activities, feasting, and trade. The Hopewell invested much more labor in construction of public places than the Adena. They built over 600 geometric mounds in Ohio alone. Some Hopewell mounds were used for astronomical observations, possibly to time special events such as the appearance of the portal to the Path of Souls. (Herrmann et al. 2014; Hively and Horn 2006, 2013; NPS 2018; Romain 2015)

The Newark Earthworks included mounds with an astronomical focus. The Octagon Earthworks (below left), is a 50-acre space surrounded by eight 550 feet long walls. The Octagon is aligned with moonrises and moonsets at the limits of a complex 18.6-year-long lunar cycle. The Octagon demonstrates that the Hopewell had a deep knowledge of geometry and astronomy and were willing and able to make significant investments to track astronomical events. (Herrmann et al. 2014; Hively and Horn 2006, 2013; NPS 2018; Romain 2015; Ohio_History_Connection 2019b)

Newark Earthworks

In addition to individual geometric mounds, the Hopewell built several clusters of earthworks across a large part of central Ohio. The individual earthworks in these clusters were built using a common unit of measure and similar astronomical alignments. The cluster of five geometric earthworks near Chillicothe, Ohio was built using a common unit of measure, similar astronomical alignments, and share common designs. Bernardini 2004

Adena and Hopewell Art

Mica

Mica was an important raw material in the Hopewell Tradition. The mineral was mined in the Appalachian mountains of the Cherokee Nation, and worked by local and Ohio Hopewell artisans into images which are compelling even today.

In the Appalachian highlands of the Cherokee Nation, quarries near Hopewellian sites at Garden Creek, Biltmore Mound, and Icehouse Bottom produced mica, quartz, and other minerals which were worked locally or traded to other Hopewell centers. (Chapman and Crites 1987; Riley et al. 1994; Stuiver and Reimer 1993); (Harari 2014) p36

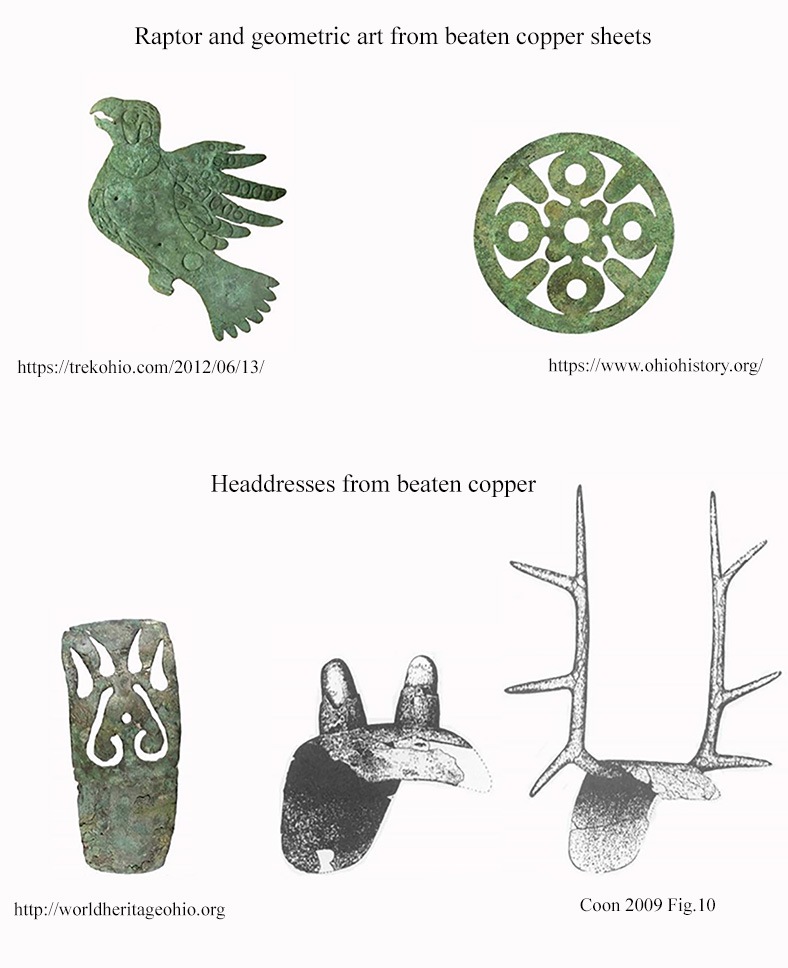

Metal

Copper and iron artifacts have been found in most Hopewell mound centers. Nuggets of almost pure copper were hammered into tools and copper sheets which were then crafted into geometric forms as well as images of humans and animals. High grade copper nuggets were needed because smelting technology (the extraction of metal from ore using heat) was unknown, and lower grade copper, silver, and iron ores can’t be cold worked. (Power 2004)

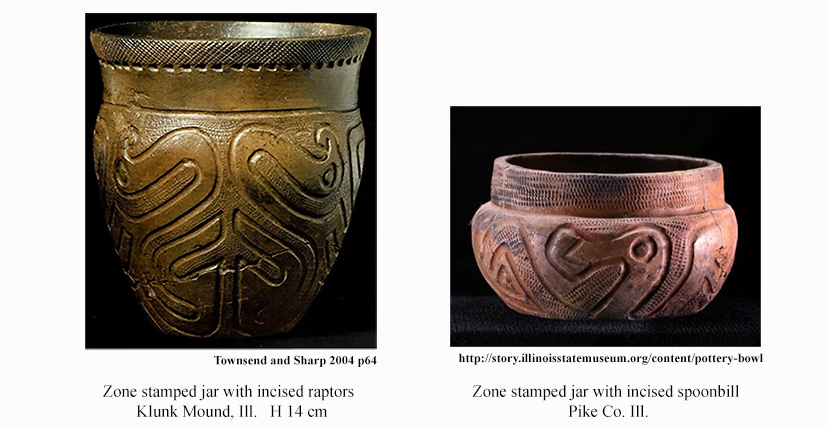

Birds were perhaps the most common subject of the Hopewell craftsmen, and over thirty different species are represented, including raptors (top left below), spoonbills, buzzards, and ducks. Other copper sheets were formed into geometric shapes (top right below). (Brown 2007; Mills 1922; Shetrone 1921; Squire and Davis 1848)

Copper headdresses (lower images) were likely symbols of political or shamanistic power. The headdress on the left shows a stylized bear paw, the center headdress represents a deer with budding antlers, and the headdress on the right a fully formed rack of antlers. (Brown 2007)

Hopewell Copper Artifacts (2,000 – 1,600 BP)

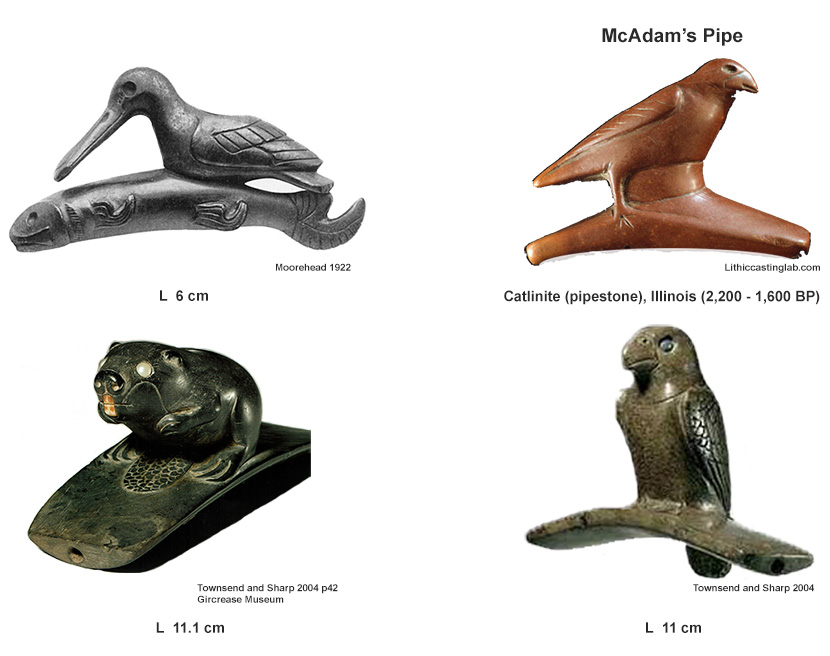

Smoking Pipes

Among the most common Adena trade goods were smoking pipes. Tobacco smoke was likely seen as a way of communicating with a spirit of the above world during religious or healing rituals.

As the Cult of the Dead evolved, smoking may have taken on more importance as a medium for communicating with a spirit of the Above World. Platform pipes, which came later, were often carved as realistic figures.

Animal Effigy Pipes

Other effigy pipes include several finely carved human heads which show Hopewell facial decorations, hair styles, ear ornamentation, and headdresses of high status Hopewell men. (Mills 1922; Squire and Davis 1848)

Human Effigy Pipes from Mound City, Ohio (2,100 – 1,500 BP)

Stone Tablets

One of the most distinctive Adena artifacts are engraved stone tablets, such as the Wilmington Tablet below, with geometric designs or stylized animal figures.

The Wilmington Tablet

Sandstone W 12.4 cm

Pigment has been found on some Adena tablets, perhaps to stamp designs on cloth or hides, or onto human bodies as templates for tattooing. (Ohio_History_Connection 2019b); (Ritchie and Dragoo 1959; Stewart 1995; Webb and Baby 1966; Webb and Snow 1974; Yerkes 1988)

Hopewell Pottery

About 4,400 years ago, the earliest fiber tempered ceramic vessels in eastern North America were made in Florida and Georgia. Ceramic technology gradually spread west to the Mississippi Valley, but fiber tempered ceramics were quite fragile didn’t have much impact on the way people lived. (Sassaman 2002; Yerkes 1988)

The Adena and Hopewell, like people of most religious beliefs, looked to higher powers for help with disease and injury, hunting, combat, courtship, and their journey to the afterlife. The powerful spirits of animals and ancestors were seen to have the power or knowledge to help with these issues if they wished.

Once shamanistic groups became dependent on maize agriculture for a major portion of their diet, natural events such as drought, flooding, and crop disease became life threatening problems which were beyond the influence of shamanistic animal and ancestor spirits.

Birdman/Red Horn

Around 1,800 years ago, a small number of Mississippian immigrants came into Ohio Hopewell territory from downriver. These immigrants from the west brought flint maize, new types of pottery to cook maize, and spiritual ideas that included the supernatural.

Next:

– Birdman, Cahokia, and the Rise of the Mississippians

– The Appalachian Highlands

References (Updated 9 18 19)

Abrams, E. (1987), ‘Economic specialization and construction personnel in Classic period Copan, Honduras.’, American Antiquity, 52, 485-99.

Adovasio, J.M., Donahue, J., and Stuckenrath, R. (1990), ‘The Meadowcroft Rockshelter Radiocarbon Chronology 1975-1990’, American Antiquity, 55 (2), 348-54.

Ahler, Stanley A. and Geib, Phil R. (2000), ‘Why Flute? Folsom Point Design and Adaptation’, Journal of Archaeological Science, 27 (9), 799-820.

Anderson, David G. and Hanson, Glen T. (1988 ), ‘Early Archaic Settlement in the Southeaster United States: A Case Study from the Savannah River Valley’, American Antiquity, 53 (2), 262-86.

Anderson, Duane C. “A Long-Nosed God Mask from Northwest Iowa.” American Antiquity, vol. 40, no. 3, 1975, pp. 326–329. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/279695.

— (1961), ‘A Glacial Kame Wolf Mask-Headdress’, American Antiquity, 26 (4), 552-53.

Bernardini, Wesley (2004), ‘Hopewell geometric earthworks: a case study in the referential and experiential meaning of monuments’, Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 23, 331-56.

— (1980), ‘Willow Smoke and Dogs’ Tails: Hunter-Gatherer Settlement Systems and Archaeological Site Formation’, American Antiquity, 45 (1), 4-20.

Bostick, Thomas (2017), ‘North American Navigable Waterways’

Chapman, B Jefferson and Adovasio, James M (1977), ‘Textile and basketry impressions from Icehouse Bottom, Tennessee’, American Antiquity, 42 (4), 620-25.

Chapman, Jefferson (1985), ‘Tellico Archaeology 12,000 years of Native American History’, (Knoxville, Tennessee: The University of Tennessee Press).

Chapman, Jefferson and Crites, Gary D (1987), ‘Evidence for early maize (Zea mays) from the Icehouse Bottom site, Tennessee’, American Antiquity, 52 (2), 352-54.

Cridlebaugh, Patricia A (1977), ‘An analysis of the Morrow Mountain component at the Icehouse Bottom site and a reassessment of the Morrow Mountain Complex’.

Dickens, Roy S (1976), Cherokee Prehistory: The Pisgah Phase in the Appalachian Summit Region (Univ. of Tennessee Press).

— (1997), Monte Verde: A Late Pleistocene Settlement in Chile, 2 vols. (Smithsonian Series in Archaeological Inquiry, 2; Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press).

Dillehay, Tom D., et al. (2008), ‘Monte Verde: Seaweed, Food, Medicine, and the Peopling of South America’, Science, 320 (5877), 784-86.

Dragoo, Don W. (1976), ‘Adena and the Eastern Burial Cult ‘, Archaeology of Eastern North America, 4, 1-9.

Fagan, Brian (2005), Ancient North America: The Archaeology of a Continent (Fourth edn.; New York: Thames & Hudson)

Farnsworth, Kenneth B. (2009), ‘The Woodland Period’, in Alice Berkson and Michael D. Wiant (eds.), Discover Illinois Archaeology (Illinois Association for Advancement of Archaeology and the Illinois Archaeological Survey).

Farris, William Wayne (1996), ‘Ancient Japan’s Korean Connection’, Korean Studies, 20 (1), 1-22.

Gibbon, Guy (1998), ‘Old Copper in Minnesota: a review’, Plains Anthropologist, 43 (163), 27-50.

Greene, Lance K. (1996), ‘The Archaeology and History of the Cherokee Out Towns’, (The University of Tennessee)

Harari, Yuval Noah (2014), Sapiens: A brief history of humankind (Random House).

Herrmann, Edward W, et al. (2014), ‘A new multistage construction chronology for the Great Serpent Mound, USA’, Journal of Archaeological Science, 50, 117-25.

Hirst, K. Kris ‘Mississippians – Mound Builders and Horticulturalists of North America Native American Farmers of the American Midwest and Southeast’, Science, Tech, Math > Social Sciences <https://www.thoughtco.com/mississippian-culture-moundbuilder-171721>, accessed.

Hively, Ray and Horn, Robert (2006), ‘A Statistical Study of Lunar Alignments at the Newark Earthworks’, Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology, 31 (2), 281-321.

— (2013), ‘A new and extended case for lunar (and solar) astronomy at the Newark earthworks’, Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology, 38 (1), 83-118.

Hudson, Charles (1990), The Juan Pardo Expeditions Exploration of the Carolinas and Tennessee, 1566-1568 (Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press).

Kelly, Robert L. and Todd, Lawrence C. (1988), ‘Coming into the Country: Early Paleoindian Hunting and Mobility’, American Antiquity, 53 (2), 231-44.

Lankford, George E. (2007), ‘The “Path of Souls”: Some Death Imagery in the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex’, in F Reilly, Kent III and James F. Garber (eds.), Ancient Objects and Sacred Realms (Austin: University of Texas Press).

Linduff, Katheryn M and Mei, Jianjun (2008), ‘Metallurgy in Ancient Eastern Asia: How is it Studied? Where is the Field Headed?’, Society of American Archaeology 73rd annual meeting, Vancouver BC Online at www. britishmuseum. org/pdf/Linduff% 20Mei% 20China. pdf, accessed (6), 2015.

Meltzer, David J. (1988), ‘Late Pleistocene Human Adaptations in Eastern North America’, Journal of World Prehistory, 2 (1), 1-51.

Mills, William C. (1922), ‘Exploration of the Mound City Group, Ross County, Ohio’, American Anthropologist, 24 (4), 397-431.

Ohio_History_Connection

Pleger, Thomas C. (2000), ‘Old Copper and Red Ocher Social Complexity’, Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology, 25 (2), 169-90.

Power, Susan (2004), Early Art of the Southeastern Indians: Feathered Serpents and Winged Beings (Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press).

Prufer, Olaf H. (1964), ‘The Hopewell Cult’, Scientific American, 211 (6), 90-105.

Ritchie, William A. and Dragoo, Don W. (1959), ‘The Eastern Dispersal of Adena’, American Antiquity, 25 (1), 43-50.

Romain, William F (2015), An archaeology of the sacred: Adena-Hopewell astronomy and landscape archaeology (Ancient Earthworks Project).

Sassaman, Kenneth E. (2002), ‘Woodland Ceramic Beginnings’, in David G Anderson and Robert C. Jr. Mainfort (eds.), The Woodland Southeast.

Saunders, Joe W., Allen, Thurman, and Saucier, Roger T. (1994), ‘Four Archaic? Mound Complexes in Northeast Louisiana’, Southeastern Archaeology, 13 (2), 134-53.

Saunders, Joe W., et al. (1997a), ‘A Mound Complex in Louisiana at 5400-5000 Years Before the Present’, American Antiquity, 70 (4), 1796-99.

Saunders, Joe W., et al. (1997b), ‘A Mound Complex in Louisiana at 5400-5000 Years Before the Present’, Science, 277 (5333), 1796-99.

Saunders, Rebecca (1994), ‘The Case for Archaic Period Mounds in Southeastern Louisiana’, Southeastern Archaeology, 13 (2), 118-34.

Schubert, Blaine W and Wallace, Steven C (2009), ‘Late Pleistocene giant short‐faced bears, mammoths, and large carcass scavenging in the Saltville Valley of Virginia, USA’, Boreas, 38 (3), 482-92.

Seeman, Mark F. (2008), ‘Predatory War and Hopewell Trophies’, in Richard J. Chacon and David H. Dye (eds.), The Taking and Displaying of Human Body Parts as Trophies by Amerindians (1st softcover edn.; New York: Springer).

Smith, Bruce D. and Yarnell, Richard A. (2009), ‘Initial Formation of an Indigenous Crop Complex in Eastern North America at 3800 B.P’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106 (16), 6561-66.

Smith, Maria O. (1995), ‘Scalping in the Archaic Period: Evidence from the Western Tennessee Valley’, Southeastern Archaeology, 14 (1), 60-68.

Squire, E. G. and Davis, E. H. M.D. (1848), Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley (New York, Cincinnati).

Stuiver, Minze and Reimer, Paula J (1993), ‘Extended 14C data base and revised CALIB 3.0 14C age calibration program’, Radiocarbon, 35 (1), 215-30.

Sullivan, Lynne P. and Prezzano, Susan C. (eds.) (2001), Archaeology of the Appalachian Highlands (1st edn., Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press).

Townsend, Richard F. and Sharp, Robert V. (eds.) (2004), Hero, Hawk, and Open Hand: American Indian Art of the Ancient Midwest and South (New Haven: Yale University Press).

Tuck, James A. and McGhee, Robert J. (1976), ‘An Archaic Indian Burial Mound in Labrador’, Scientific American, 235 (5), 122-31.

Waters, Michael R. and Stafford, Thomas W., Jr. (2007a), ‘Supplemental Online Material: Redefining the Age of Clovis: Implications for the Peopling of the Americas’, Science, 315 (5815), 1122-26.

— (2007b), ‘Redefining the Age of Clovis: Implications for the Peopling of the Americas’, Science, 315 (5815), 1122-26.

Webb, William S. and Snow, Charles E (1974), The Adena People (1st edn., 6: Univ. of Tennessee Press).

Webb, William S., Snow, Charles E., and Griffin, James B. (1974), The Adena People (3rd edn.; Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press).

Webb, William S., et al. (1966), The Adena People No. 2 (3 edn.; Columbus, Ohio: The Ohio Historical Society).

Weiland, Jonathon (2018), ‘Appalachian Mountain Geologic History’, (Stanford, California).

Wikipedia

Willey, Gordon R. (1966), An Introduction to American Archaeology Volume One: North and Middle America, ed. David M. Schneider (Prentice-Hall Anthropology Series; Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall).

World_Heritage_Ohio (2014), ‘Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks’. <http://worldheritageohio.org/hopewell-ceremonial-earthworks/>.

Yerkes, Richard W. (1988), ‘The Woodland and Mississippian Traditions in the Prehistory of Midwestern North America’, Journal of World Prehistory, 2 (3), 307-58.

Dickens, Roy S (1976), Cherokee Prehistory: The Pisgah Phase in the Appalachian Summit Region (Univ. of Tennessee Press).

Greene, Lance K. (1996), ‘The Archaeology and History of the Cherokee Out Towns’, (The University of Tennessee).

Hudson, Charles (1990), The Juan Pardo Expedition’s Exploration of the Carolinas and Tennessee, 1566-1568 (Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press).

Keel, Bennie C (1976), Cherokee Archaeology: A Study of the Appalachian Summit (University of Tennessee Press).

Purrington, Burton L (1983), ‘Ancient mountaineers: An overview of prehistoric archaeology of North Carolina’s western mountain region’, The Prehistory of North Carolina, North Carolina Division of Archives and History, Raleigh, 83-160.

Appendix 1

Cherokee Treaty of 1759 and Mooney 1900 Cherokee Country map

https://portola.press/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/3acbb-cherokee-treaty-of-1759-and-mooney-1900-cherokee-country-map.pdf

David Scott, Lauren Banish, David Brown, The Stanford Cherokee Club